During the preparation of my NIH proposal in May 2018, I started a OneNote document to organize the information I gathered. These are my notes and some tips. Hope it can be useful to new investigators. I got lucky with NIH only once, so I am not that “seasoned”. This is based on my personal opinions, experiences, and lessons.

1. Suck it up and write it

- I use one Microsoft Word document to write all the components: Project Summary, Narrative, Specific Aims, Research Strategy, References, Facilities, Equipment, Personnel justification, Resource Sharing Plan, etc. Start a new page for each component, so that you can print out only the pages for the component to a PDF file. Google “Print to PDF” if you do not know how to do it.

- Save your Microsoft Word document often, and create multiple copies with versions. Large files can get corrupted. Your hard drive can crash. Email yourself new versions as you write. Or use Google drive. When things go wrong they tend to go wrong at the worst of time.

- Write the summary and specific aims pages and ask for feedback from colleagues/friends. If you don’t have a good idea, preliminary data, and a solid research plan, go back to your research work or literature reading. Don’t waste weeks or months on an idea that has little chance. Go fishing, golfing, or jogging. You may have your aha moment!

- Grammarly.com can help with grammatical issues, better than Word. It works as a plug-in to Microsoft Word. But ask someone to proofread. I even had an undergraduate student read through my proposal and he was very helpful.

- Use EndNote to manage references.

- The Project Summary and Specific Aims are vital. I found it useful to read them aloud, over and over again. If it sounds unnatural, try put it differently.

- Cross-references to Tables and Figures in Word is helpful but can be tricky. You have to select the entire document and “Update Fields”. I have a “(See Table 2)” in my proposal that looks great in Word. But when you print or generate PDFs, it becomes “(See Error! Reference source not found.)“ Since it is buried on page 4, a grant specialist only found it after the proposal was submitted. We had to retract it at 4:15pm on the due date. Only to mess other things up. Then the computer decides to lock me out because I didn’t update my network password properly …

- Get support letters and Biosketches from collaborators early.

- Try not to fill in as much text in every square inch. Make it reader-friendly and organized. Less is more.

- Use short sentences.

- I found it more efficient to sleep well and keep playing tennis throughout the process. A high-quality proposal demands sharp, focused, and creative minds. Somethings just cannot be accomplished by simply working “hard” overnight, as there is a lot of decision making, not simple mental labor.

2. Choose an award mechanism

According to NIAID, “An R01 is a mature award that gives you four or five years of independent support, enough money (as well as time) to complete a project, publish results, and start writing your next application in time to get an award before the funding ends.” “If you have preliminary data, we recommend an R01.” “Drawbacks for Smaller Awards (R21, R03) These awards are primarily for established investigators who want to complete a limited project, for example, a pilot or feasibility study. NIH did not design them to help you establish a research career. Nor are these smaller awards easy to get.” See NIH success rates.

3. Set a deadline!

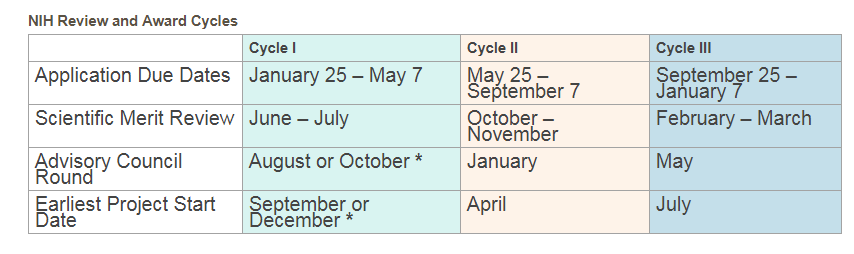

Most NIH grants have three cycles a year. Source

4. Search for a funding opportunity

- Parent Announcements (PAs). NIH does not micromanage like NSF. Most NIH grant proposals are investigator-initiated. Many proposals are not responding to specific funding opportunities (RFPs/RFAs), but to generic PAs, such as the PA for R01, PA for R21, and PA for R15. These links as of June 2018. To get the most updated versions, I often just Google “NIH parent R01”. Note that not all NIH centers participate in all PAs.

- Funding opportunity announcements(FOAs) by specific centers can be searched here.

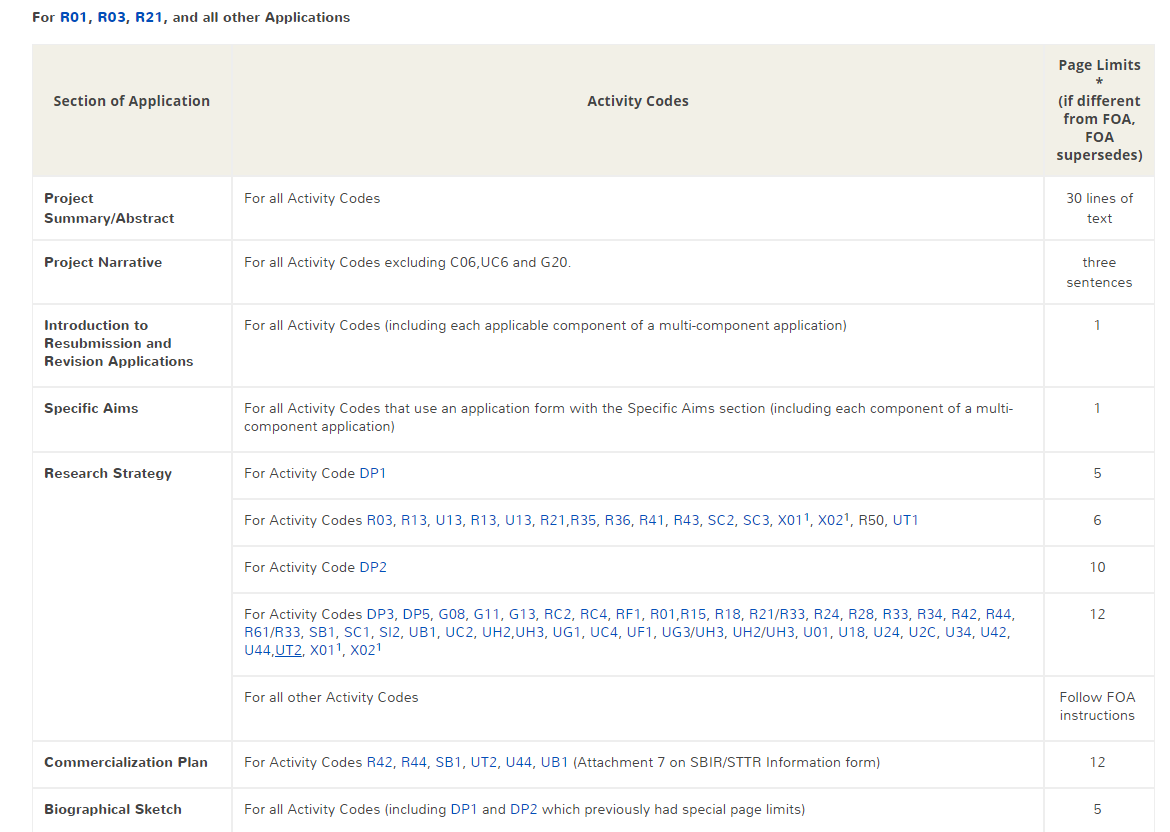

5. Page limits

6. Sample applications are very helpful

Take a quick look at these examples. I learned a lot from them. It is much more efficient to learn from examples than reading the guidelines. If you know someone that has a successful proposal. Email him/her to ask for a copy. Many people share.

7. Use Proposal Guides as a reference

It is available as a big PDF file or section by section.

8. Use SciENcv to generate your biosketch

Most of us have old versions. But if your is a few years old, try SciENcv! It generated an updated, nicely formatted biosketch with links to publications. And a link to all my papers on My NCBI’s My Bibliography.

9. Use Assisted Referral Tool (ART) to identify CSR study sections

You paste your project summary to the ART tool, and it recommends study sections and NIH Centers. I was surprised by how good this tool is. Hey, it is 2018! AI is everywhere. Specifying study sections and Centers are optional. This is one of the many reasons I like NIH. They make it easy for you. NSF, on the other hand, is so complex with millions of funding opportunities to search for, billions of jargons to decode.

10. Submission

- Develop a budget with the help of someone from the budget office. Or use their template Excel file.

- Start the institutional routing process early. You only need a summary and a budget.

- Log in to era Commons. Your institutions can create that for you.

- After logging in to era Commons, use ASSIST to navigate the submission process. Some helpful information on ASSIST is here.

- Once you have a decent draft of the proposal, complete with all required components, send it out to someone ( a colleague or a grand specialist) to help edit. While waiting for edits and feedbacks, start working on the forms. Generate PDFs for all the components and upload them to ASSIST. Also, fill in all the required forms. You may need some of the optional forms, like the Modular Budget. Now you have a complete application package that theoretically could be submitted. Going forward, you only need to replace the key PDFs.

- Ask a grant specialist to check the application package for errors and compliance. You can go back to revise your Word document.

- Try to finish everything two days before the deadline and let them submit. Things can and will go wrong if everything is pushed down to the last hour.

11. After submission

- While you are working on it, your proposal is in “Work in Progress” status. It has an ID like “ASSIST 321779”. Make it into “Ready-for-submission” status, so that your signing official can do the actual submission.

- Once submitted, it is assigned a GRANTs.gov ID like “GRANT12643962”. You will receive some automatic messages of status changes and error and warnings from both ASSIST and GRANTS.gov. These IDs are especially useful when you retracted an application, fixed the errors and re-submitted.

- ASSIST is just for submission. After submission, you check for status and error messages in the Status menu in era Commons.

Once submitted, relax and enjoy life. Try not to check the status every 5 minutes like me! You will not get a score until 4 months later (see the table below). If you get a decent score but not awarded, you can revise the proposal and try again in the next cycle. Similar to the way you revise papers, focus on addressing the criticisms, as the reviewers may be the same. This is another reason I like the NIH system. It is relatively quick.

At NSF, one of my proposals was listed as pending for 13 months with zero feedback. I only realized that my “no-news-is-good-news” mood was foolish after I emailed them! NSF program officers do not even return my emails sometimes. Sorry for a sore loser’s complaints. But the NIH system is relatively more friendly.

Please let me know if you have questions or different opinions by commenting below.

Link Note: Picture is from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9BCvEo7J8s